Daphne Plessner and Emily ArtinianSeptember 2019

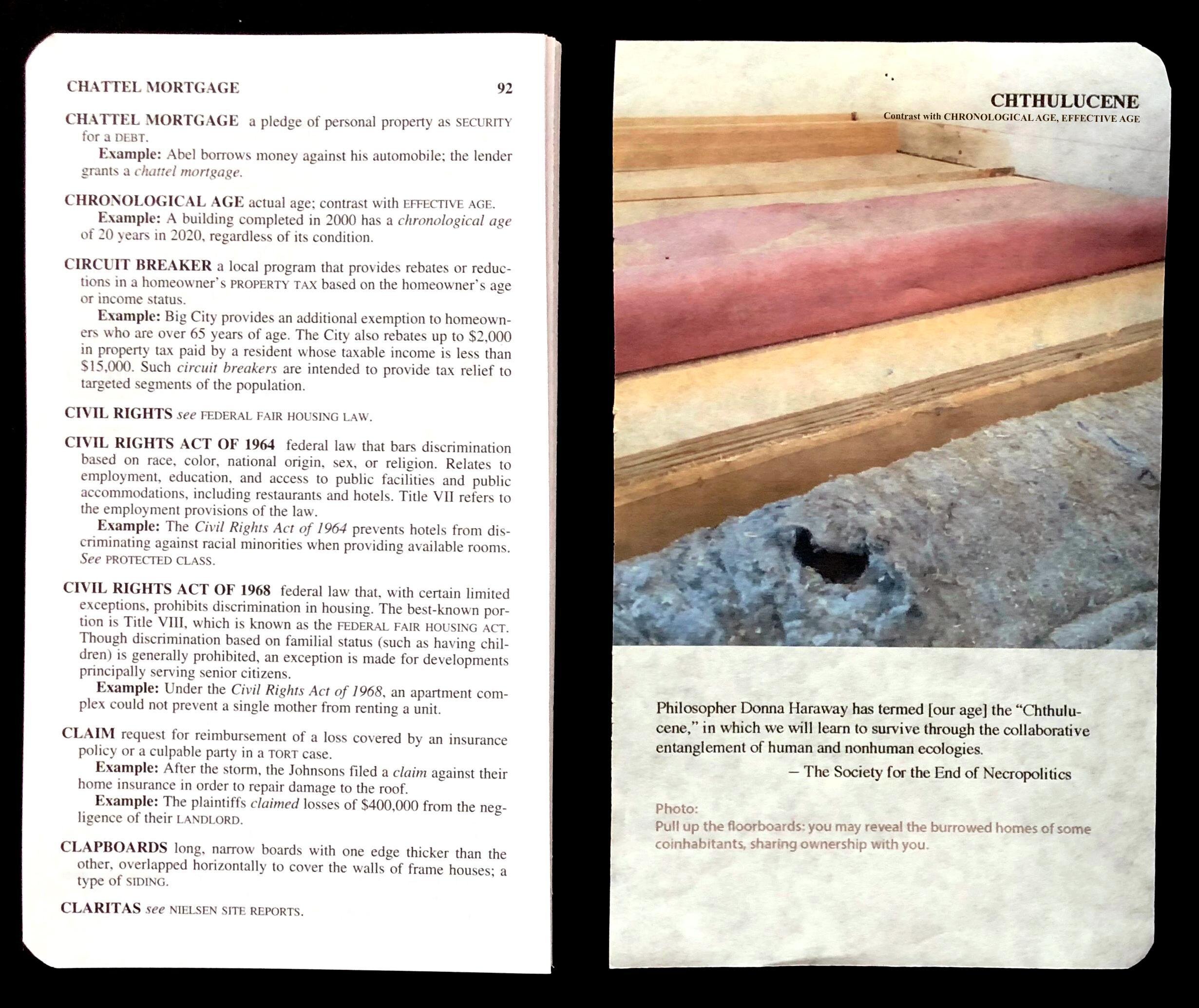

Street Road Street Road is an art space in Pennsylvania created in 2011 by Emily Artinian as an evolution of – and with resources inherited from – a family real estate business. For the past 8 years it has hosted projects that relate directly to and challenge the problematic, capital-driven activity which produced its possibility. The space was named for the toponym by which the site is located (Street Road, aka PA Route 926) – specifically for its aptness to the overall project: etymologically ‘Street Road’ derives from via strata, or ‘paved road’, encoding histories of human and land intertwinings, particularly human impulses to map, possess, use and constrain place and space. The environs of Street Road, an hour’s drive west from Philadelphia, might be characterized as a cacophony of ruralities, exurbs, suburbs, and throughways, all in cheek-by-jowl proximity, intermeshed with each other to the point of indistinction. This interstitial quality has been a fertile context for thinking differently about and un-seeing simplistic rural/suburban/urban framings. And it has been a good starting point for what has become a central initiative of Street Road, a project called Clouded Title. Clouded Title: an overviewClouded Title is a series of dialogues, exhibitions and publications centered around land ownership – its ambiguities, histories, and areas of contestation. Different landholding models, particularly those emphasizing social and ecological relationships over private possession (or any possession), are explored. Begun in 2017, the project is led by Daphne Plessner and Emily Artinian. The work grew out of their informal discussions around ownership, and came into focus within Street Road’s overall project of troubling received wisdom around real estate investment and speculation. The term ‘clouded title’ is used in real estate law and practice to indicate a situation in which title to a plot, parcel, or object is not free and clear for one reason or another. The Clouded Title project embraces this phrasing and takes it as a metaphor applicable to most ‘property’, which always comes with complex genealogies of ‘ownership’. This approach opens the possibility of understanding ownership as a kind of narrativity, even a set of fictionalities, written and re-written, and read and re-read in radically different ways over time.In addition to taking up the term ‘clouded title’ as a lens for understanding ownership of land or property, this can also be understood as a methodology for our process. There is an unprecedented amount of re-thinking around land claims taking place globally today (1), in the present and also retrospectively (for example, with support for land reparations entering into current campaign rhetoric in the US for the first time, or in the rapid, global, expansion of neo-colonial appropriation of lands and ‘expulsions’ of peoples and animals from locales (Sassen, 2014)). However this work often remains extremely siloed within separate disciplines. Therefore, central to the Clouded Title project is building multi-perspectival understandings of ownership, through the participation of diverse groups, and especially alongside artists who work in this terrain.The project facilitates conversations between and amongst different participants, and we show portions of the growing archive of this material in exhibition contexts that embrace a fluid idea of visual art and archive. The work has been presented publicly in several spaces: as a workshop on Pender Island, British Columbia, an exhibition at Street Road, and as part of the panel Reconsidering Place: troubling the urban/rural binary for artist practices and organizations hosted by Plessner and Artinian at Common Field’s 2019 convening in Philadelphia. Participants in Clouded Title to date, to name a few, have included The School of Living, a community land trust with locations in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia; Our Spaces: the foundation for good governance of international spaces, a group who focus on the Antarctic, Outer Space, and other international treaties; members of the W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation in Canada; and environmental lawyer and academic David R. Boyd. A significant Clouded Title convening was a workshop in which these last two were in dialogue around colonial notions of treatied and unceded lands versus Indigenous peoples’ relations to land as a non-human being.Clouded Title’s growing archive of materials (recorded Skype sessions, written exchanges, etc.) is in the process of being developed to be made publicly available through online and print sources. Also in development is a more formalized platform for ideas exchange and inclusion of new participants. The following will give a brief overview of two of our own art projects developed within this framework – The Real Estate Dictionary (Artinian), and Citizen Artist News: Clouded Title (Plessner). We will then introduce briefly two other artists’ projects that are included in Clouded Title, and that have taken an embodied approach to research and making, an exceptionally good ground for thinking through questions around ownership.The Real Estate Dictionary: Improved Edition A collective editing, convened by Emily Artinian.Barron's Dictionary of Real Estate Terms is currently in its ninth edition. A reference text in widespread use in the real estate industry in the U.S. for decades, this capital-centric source omits most concepts related to collective ownership in any form, steers well clear of land appropriation, current and historic, and is resolutely anthropocentric and deaf to ecological concerns. The project’s subtitle plays on the pervasive use and understanding of the word improvements in the field – as the dictionary editors have it: “those additions to RAW LAND, such as buildings, streets, sewers, etc., tending to increase value.” The tacit and a priori understanding of land as an object for possession, extraction, and use, and of value in a blatantly reductive sense, is entrenched in the field, and the definitions throughout bear this out. The Real Estate Dictionary - Improved Edition, therefore, begins at an obvious place: with an unbinding of the book. This opening is a start, making room for a process of editing, deletions, additions, etc. An insertion: ‘Chthulucene’, with reference to other Real Estate Dictionary entries such as ‘Effective age’

Editing in progress / installation view: the terms ‘Dominant Tenement’, ‘Partial Taking’, and ‘Hell or High Water Lease’ are reconsidered through a process of collage, as exhibited at Street Road, 2018.

A collective process: the potentially infinite, Borgesian undertaking of rewriting a dictionary is yes, mad. Librarians are needed. Artinian sees this as her work but others – those taking part in Clouded Title, for example – are invited to join in to point out and/or to contribute elided terms, ideas, and knowledges, and to delete or refine and redefine existing entries, and also to add personal stories or situations related to land ownership.The book will eventually be re-bound and the new edition will be sent to the publisher and editors, potentially in successive editions. The insertion of such a revised document into this and other arenas specifically within the territory of real estate practice (such as trade fairs, conferences, business associations) is important to the project, especially as it is in these spaces where normative understandings go so unchallenged and unconsidered.Left: Copies of Citizen Artist News: Clouded Title. Right: Clouded Title Research Workshop, panel discussion and pop-up installation of art works, Community Hall, Pender Island, B.C., Canada, April, 14, 2018.

Citizen Artist News: Clouded TitleCitizen Artist News is a series of (three) art interventions in the form of broadsheet newspapers (2018 - 2020). These interventions are targeted at a small local settler community of Pender Island, located on the South-West tip of British Columbia, Canada. Citizen Artist News: Clouded Title focused on the problematics of British colonial appropriation of lands and the specifics of residing on Pender Island, which is within the unceded territory of W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation. 1000 copies of the newspaper were distributed to the homes of local island residents of Pender in April, 2018. This was followed by a formal launch, pop-up exhibition and research workshop with Street Road that took place in the local community hall on the island (April 14, 2018). Citizen Artist News: Clouded Title invited island residents to participate in a public ‘thought experiment’ that detailed the historical and current colonial rationale for the appropriation and (private) possession of Indigenous lands within this region (W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation territory) by the Crown and as purportedly sanctioned by the Douglas Treaty: North Saanich (1852). It contrasted this Statist narrative of the Treaty with W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation tellings of their own history of its making – a history that sharply conflicts with State and settler beliefs, as will be discussed further below.One aspect of the intervention highlights how the Douglas Treaty embodies British cartographic vocabularies that enfold claims to land, such as the imaginary of enclosures, discrete patches of terrain marked by borders, agrarian virtue, designations of ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ habitations etc. These notions of ‘ownership’ that are captured in concepts such as ‘rural’, ‘urban’, ‘countryside’, ‘wilderness’, etc., continue to inform and be performed in multiple ways. To give some context: currently, Pender Island is designated as a ‘rural’ community, but it is in fact a highly populated ‘suburban’ community. In the past 40-years there has been an escalation of suburban development, brokered and promoted through local government. There is not only a direct correspondence between the earlier phase of colonial governmental agendas to accelerate (British) ‘settlement’ of (unceded) territory as a Statist technique of claiming Indigenous lands (as expressed through the Treaty from the 1850s and on), but also, the focus in recent decades has been on the State’s brokering of ‘real estate’ as an anchor for global financial capitalism and corporate acquisition (Sassen, 2014). The fact that Pender Island is within W̱SÁNEĆ territory is simply not visible within the region, nor is it acknowledged within local systems of government (e.g., Island residents do not pay land taxes to the W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation – as we should – but only to the colonial government; land is sold or ‘developed’ within their territory regardless of the concerns of the W̱SÁNEĆ people etc.). The designation of Pender Island’s ‘rurality’ also determines the domain of local government (voting districts, gerrymandering etc.) that continue to suppress W̱SÁNEĆ First Nation presence and systems of governance within their territory. These colonial techniques of power are deeply embodied within settler culture and underpin assumptions and performances of entitlement to land, that in turn, are instituted as jurisdictions of the State. Indigenous practices of governance and relations to land are therefore actively suppressed and negated within this region. For example, W̱SÁNEĆ relations to land are based on a system of stewardship and responsibility to care for the is/lands as a living being. The islands (including Pender Island) are understood as ‘ancestors’ and kin relations. Citizen Artist News Clouded Title therefore made visible the implicit biases contained within the Treaty’s colonial interpretation as a purported sale of land and the ongoing asymmetrical practices of appropriation that of course favour the settler community. To critique the distortions within the fiction of land ‘ownership’, the newspaper foregrounded W̱SÁNEĆ writers and other Indigenous scholars who instead describe the Treaty as a ‘Peace’ Treaty: a history and interpretation that exposes how and why the Treaty, as a troubled document, continues to disenfranchise the W̱SÁNEĆ people. The newspaper highlighted the central problem of State and settler (mis)interpretation as having the effect of suppressing W̱SÁNEĆ tellings of the Treaty’s meaning and history. The newspaper also points up how these different readings of the Treaty continue to shape (skewed) relationships that persist today. For example, on the one hand, narratives of the State’s appropriation of land as a treatied ‘sale’ dominates the imaginaries of island residents as a space to which residents ‘belong’. The (false) narrative of ‘ownership’ sanctions colonial-capitalist assumptions of possession and it underpins beliefs about belonging and membership to the Canadian State. On the other hand, through the lens of a Peace Treaty, the W̱SÁNEĆ people understand this moment as a set of promises that were to be reviewed annually (i.e., rents etc.), with the hope of establishing equitable relations between British settlers living within their territory. Through W̱SÁNEĆ eyes we see that the Treaty is in fact a means for framing and navigating complex relationships with settlers, not a ‘contract’ for the purported ‘sale’ of land. Citizen Artist News: Clouded Title therefore invited readers to think through the false logic and claims to the possession of W̱SÁNEĆ lands. It drew attention to local (Pender) Island residents’ performance of the fiction of a land sale and settler inscriptions of virtuous (British) colonial history and belonging (as manifesting in nascent grass roots Historical societies etc.) where identity, entitlement and relations to land pivot on a conception of land as a capital ‘resource’ braided together with idealizations of private property as a “rural idyll” (building of ‘Dream homes’, outdoor recreational activities etc.). From the 1990s to the present day especially, the island has been exploited as desirable ‘real estate’ and a leisure-retirement, ‘safe’ and ‘untroubled,’ quasi-‘gated,’ community. Pender Island is also primarily a retired, middle class, community with a (now) majority of residents of British ancestry. However, it is also something of a riddle, with grassroots organizations (historical societies) that are proactively engaged in continuing the inscription of the island as a narrative of British-Canadian colonial habitation and virtue. The art intervention therefore was targeted at residents to trouble these assumptions in fundamental ways. The newspaper and the workshop together therefore drew attention to the ongoing epistemic violence of colonial narratives within this local community.Following the initial posting of copies to residents on the island, a one-day pop-up research workshop was hosted by Emily Artinian (Street Road) and me. This ‘deterritorialized’ event was in dialogue with Street Road, not as a quasi ‘educational outreach’ program, but as a means of extending the conversation and interrogation of ‘ownership’, with the aim of examining local (Pender Island) claims and understandings of place. As a push back to the capitalist-driven concept of ‘ownership that prevails within ‘Canada’, the workshop included a pop-up exhibition of printed matter of the participating artists’ in Clouded Title. We also co-chaired a panel discussion with Mavis Underwood (Member of Council, Tsawout First Nation) and Elder Earl Claxton Jr. (Tsawout First Nation), David Boyd (Law professor and Special Rapporteur for Human Rights and the Environment for the United Nations) and Robert Clifford (Legal Scholar specializing in Indigenous Law, Tsawout First Nation). The discussion pivoted on the implications of the Douglas Treaty by exploring different starting points, perceptions, and critiques of the notion of ‘ownership’. In summary, the idea of developing an art intervention that engages with the experience of place emerged from the pressing reality and tacit complications of living within a community that is characterised through British colonial claim-making that also suppresses knowledge of the locale as within W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) First Nation territory. These islands are in fact unceded. However, they are regarded by the State and its subjects as if they are the property of, initially, the British Crown (1850 – 1982) and now, the Canadian State (1982 – present). The fact that these lands are therefore ‘clouded in title’ is a source of ‘cognitive dissonance’, so to speak. That is, the island community is inscribed and celebrated through a narrative of British colonial subjecthood and much of what is visible as socially, politically and culturally significant is framed through the lens of its (British) colonial subjects. There is much public pride, display and celebration amongst, for example, Scots and English settlers of their own (family) history of the island and the performance of Anglo-Canadian nationalist sentiments that are then mirrored in the image of the Province and the State. The fact of this privileging of British ethnic histories and claims to possession of land and belonging (with a focus on historically storied virtuous farming families), continues to obfuscate the reality of not only living on appropriated W̱SÁNEĆ lands but also aggressively flattens the complexity of other ethnic histories and peoples that have resided within this space from the 1870s to the present day. Part of the motivation for developing the art intervention within this small community therefore is to think through the aesthetic experience of this troubled reality and examine how it manifests within resident’s larger claims to belonging and membership of the Canadian State. I also feel a responsibility to the W̱SÁNEĆ people not to tacitly endorse or perform the ongoing epistemic violence of settler appropriation when residing on W̱SÁNEĆ territory by saying and doing nothing to contest the fiction of settler entitlement. Walking Art Practices and OwnershipA main strand of Clouded Title’s examination of ‘ownership’ is dialogues and workshops with artists whose practice involves the act of walking as a medium for aesthetic engagements within a terrain and meditations on time that issue from experiences of one’s bodily movement through a landscape. We are especially interested in walking being explored by artists as a mode of claim making.Walking with Carol Maurer, February 2018, Dorchester County, Maryland

This aspect of ‘ownership’ was brought to light first through the work of Carol Maurer and her project titled Walking Forward, Looking Back. Artinian and Plessner accompanied Maurer on the first stage of her walk from her ancestral family estate on the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Street Road’s premises in Chester County, PA (the walk took place in stages over several months in 2018). The project is rooted in Maurer’s own family history of slave ownership and agrarian British colonial appropriation of lands within the region, enfolded in an ancestral network of legislators working through Washington DC, reaching back to the 18th century and continuing until abolition. Her family history and the terrain are entwined in a complex mix of the historical and political violence of enslavement and exploitation of African-American bodies and the family’s direct involvement in the State’s management of slaves as a primary ‘industry’ of the capitalist economy. The results of this (personal, political and economic) history are inscribed in the terrain but are also ironically rebuked by the current environmental degradation of the land. What was distinctive about the first phase of this journey was that it began at Maurer’s family home and its former farm lands, now sinking under rising waters. The estate is now markedly desolate and riddled with dying pine trees, hemmed in by oily, littered, shorelines within a larger, exhausted landscape surrounded by a dead sea. This initial stage of the walk retraced the roads and pathways that both Maurer’s ancestors and slaves would have traversed. The day’s walk aptly ended with a visit to the Harriet Tubman Museum, located along the escape routes that slaves, such as Tubman, would have followed, signposted by the unsanctified graveyards of those even less fortunate.Ownership by Walking: Traversing the Ruins, detail

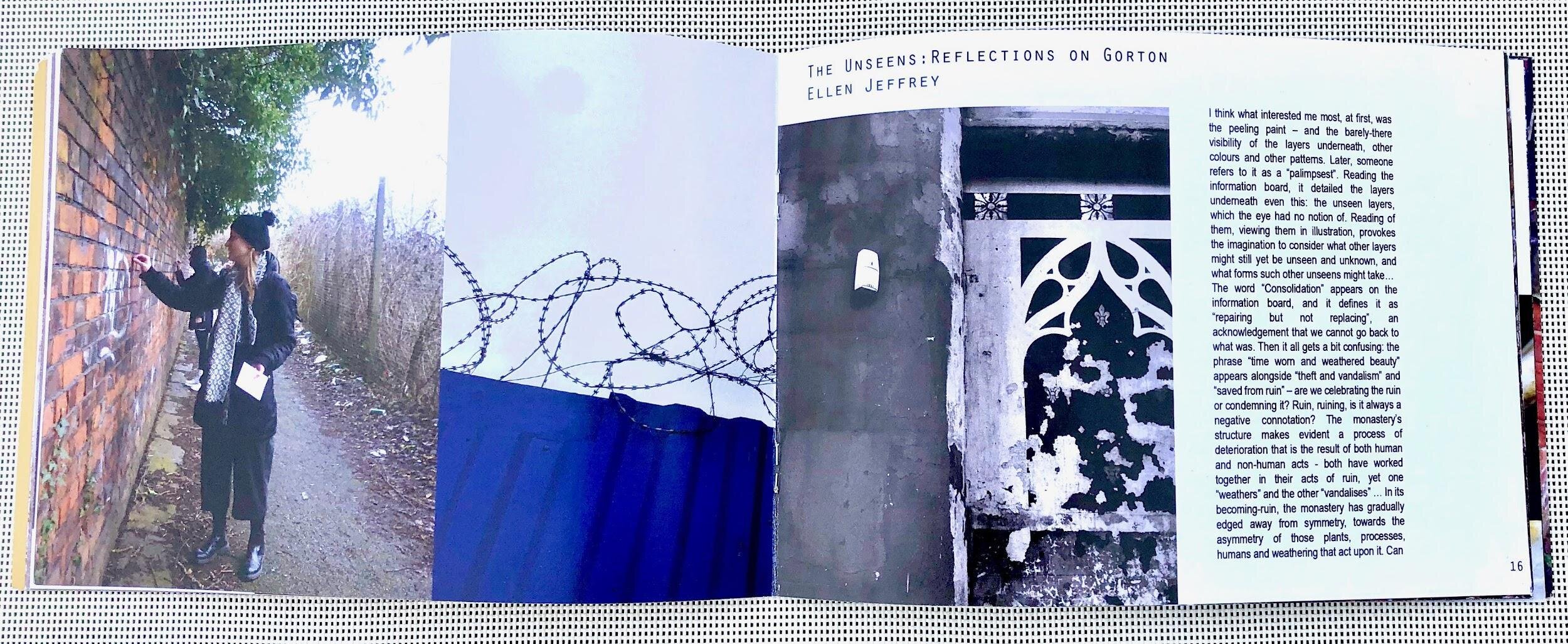

Clusters and Entanglements is a group of research students based in Manchester, UK who run a series of embodied reading workshops, with a focus on environmental and eco-phenomenological debate. With Clouded Title, the group developed a one-day workshop, centered on a walk around Gorton Monastery and its environs, on the eastern side of Manchester. Related readings included Tim Edensor’s Sensing the ruin (2007), Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s Stone, an ecology of the inhuman (2015), and Rebecca Solnit’s ‘Detroit Arcadia: exploring the post-American landscape’ (Harpers, 2007). Subsequent to the walk, the group held several online discussion sessions with Clouded Title, developed individual blog entries around the walk and readings, and also published a print publication: Ownership by Walking: traversing the ruins (2017) with contributions from Anne Caldwell, Lin Charlston, Sara Davies, Claire Dean, Mark Dyer, Sarah Hymas, Ellen Jeffrey, and Gemma Meek. Full blog entries can be found here.The workshop and discussions posed a number of questions: do we become owners in some way simply by walking through and inhabiting a space? What is the nature of ownership if you think about it this way? Is ownership more to do with power or with a sense of belonging? Several strands of thinking that emerged in our discussion processes and the group’s writing have been particularly notable for Clouded Title, as additional ways of thinking about ownership. First is a focus on simple, direct and embodied acts of inhabiting space as a form of ownership – considering ‘possession’ through a phenomenological lens. Mark Dyer, for instance, explores sound as claim making in the essay ‘Hearing the ruin: ownership through sound’, wondering: ”In such a space [Gorton monastery], I could shout out. The sound would travel, echo, and envelope the space and those within it. Is this ownership or inhabitation? The former suggests an imposing of self and voice upon those that share the space, whereas the latter feels like a borrowing with consent. I do not shout.” Secondly, this work has brought into focus consideration of non-human agency, and the many varied non-human kinds of possession, that often go un-remarked, un-seen. Anne Caldwell reflects on the walk and the Solnit reading:My companion says she notices all the living things…. This point of view makes me see the ‘ruins’ and dereliction in a new light. They are greening over. Rebecca Solnit talks about this process in Detroit, and how the remaining urban population is turning abandoned spaces into gardens and places of food production: ‘in traversing Detroit, I saw a lot of signs that a greening was underway, a sort of urban husbandry of the city’s already returning to nature’. …. Later over lunch we discuss the different meanings of restoration and conservation. I think of how the ‘non-human’ world is reclaiming the spaces we choose to abandon.’ To date the discussions hosted by Artinian and Plessner have brought to attention the palimpsestic nature of place, prompting the idea of ownership as palimpsestic. This has emerged as an important thematic for Clouded Title overall. Inscriptions and traces point in a layered and fragmentary fashion to not only the social, political and cultural elisions that have occurred (and continue to occur) but also to recurring normative (often Statist) narratives of belonging and membership that are subtended by various forms of claim-making and ‘ownership’ (of land). What is striking in all of these art projects is that they make apparent how the actual place reveals more complex histories through inscriptions. Part of the purpose of Clouded Title is to establish a platform for art practices that help to shape new conceptual and performative tools for contesting colonial-capitalist imaginaries of ‘ownership’ and the above outlines just some of the seeds and shoots that have emerged in these past two years of Clouded Title’s activities. Our intention is to work further with our growing network and archive. We also welcome ideas and proposals from artists and others for future participation.(1) Some notable recent texts that have informed this work: Graham, J (2017) Architecture Against a Developer Presidency; Kiel, R (2018) Suburban Planet: Making the World Urban from the Outside; Reid Ross, A (2014) Grabbing Back: Essays Against the Global Land Grab; Sassen, S (2014) Expulsions:Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy; Stein, S (2019) Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State.cloudedtitle@streetroad.org / emily@streetroad.org / fdplessner@shaw.ca